Cavaliers' Jarrett Allen is a straight shooter on and off court

By Yaron Weitzman

FOX Sports NBA Writer

Editor's note: This story was originally published on Feb. 3. On Monday, Jarrett Allen was named to the 2022 NBA All-Star team.

One thing you should know about Jarrett Allen is that if you ask him a question, he’s going to answer it as truthfully, honestly and — this is the key part — literally as he can.

This is the sort of thing that sounds obvious and that we think everyone does but is actually a rare trait.

For example, how often will you skew your answers toward what you think the person doing the questioning wants to hear? Will you tell a loved one that the dress looks just OK? Or a boss that his idea is awful? Or a barber that you don’t agree with their scorching basketball take?

Most of us, at our core, have an urge to please, to appease, to deliver the right answers to questions. And, more importantly, we have a radar for when such answers are required.

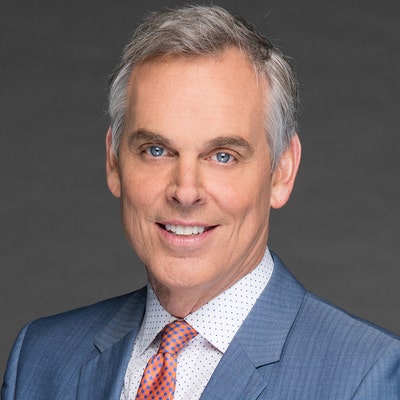

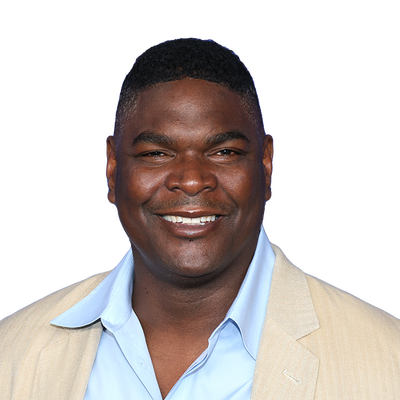

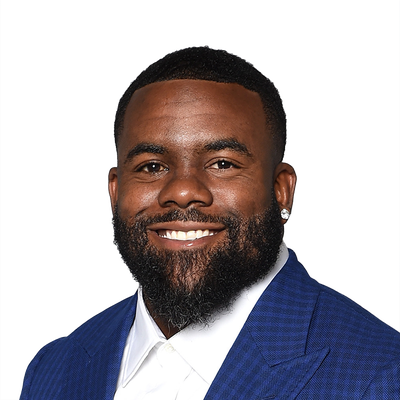

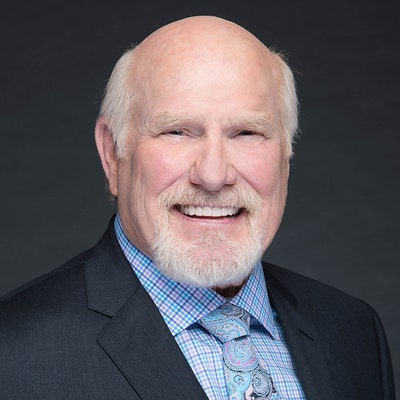

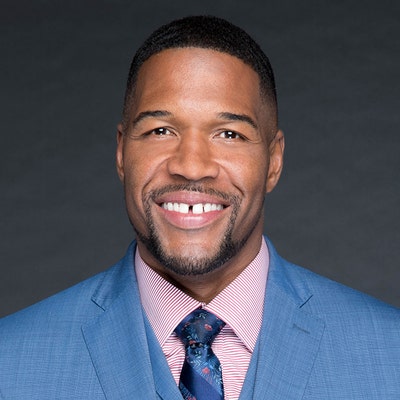

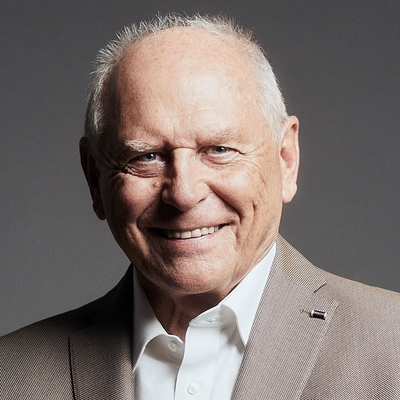

Even before Jarrett Allen was drafted, anyone who asked him a question found out that he would respond honestly rather than spewing clichés. (Photo by Stacy Revere/Getty Images)

All of which brings us to May 2017, to a conference room in a swanky downtown Chicago hotel, where Jarrett Allen, a 19-year-old prospect at the time in town for the NBA’s annual draft combine, was seated across from about a half-dozen team decision-makers.

He doesn’t remember the specific team. Or maybe he does, but he’s not 100 percent sure. Because of that, he’s not comfortable saying. What he does remember, though, is the question:

"Can you live without basketball?"

That's what someone in the room asked him. Allen, you see, had picked up a reputation of being, well, a nerd. He had interests outside of the game. Computers. Math. Space.

Yes, space.

It didn’t matter that Allen’s coaches at the University of Texas had stressed to every NBA scout who had come through Austin that while Allen wasn’t the sort of player who asked to have the gym open at midnight three times a week, he was a player who did everything asked. More than that, he would push to understand why it was being asked.

"He’s probably the best learner I’ve ever been around," Shaka Smart, the head coach of Allen’s Texas team, told me.

But, well, Allen was still a gangly near-7-footer who loved math and science. Which, to some evaluators, was as bright red as a flag could get. Hence the question: Could this giant geek live without the game?

"I was thinking, like, I got my brother, I got my mom, I like doing other stuff," Allen recalled recently. "It didn’t occur to me that they were trying to get this answer out of me. I was just answering honestly."

He loved basketball, but could he live without it? He didn’t even understand the question. Water was something you couldn’t live without. Family was something you couldn’t live without. But a game? Who couldn’t live without a game?

So he answered truthfully, which, he assumed, is what these men wanted to hear. Yes, in this hypothetical world, if the game of basketball were taken from him, he could, indeed, go on living.

"It never ever occurred to me that I had failed the interview," Allen said recently.

He learned he did only after the answer filtered its way into the NBA gossiphere and back to Smart, who told Allen that it was being interpreted as revealing a lack of competitiveness and interest in putting in the required work.

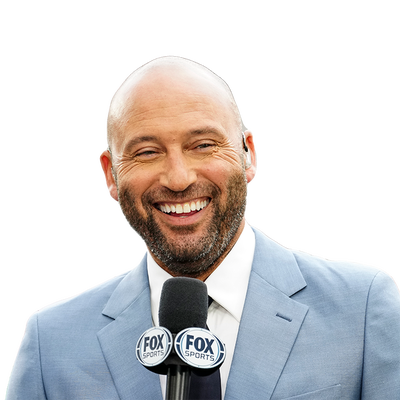

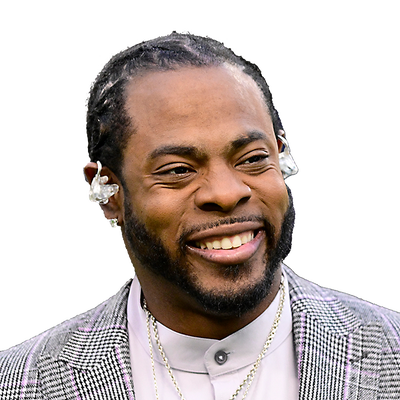

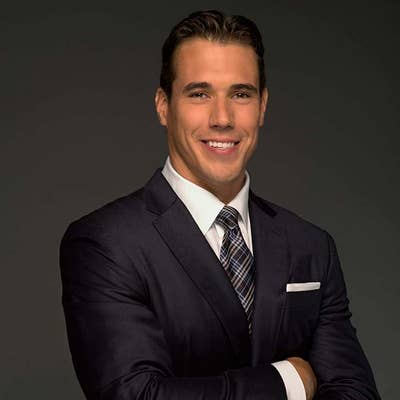

Shaka Smart, who coached Allen at Texas, calls him the "best learner" he has been around. (Photo by Michael Reaves/Getty Images)

Allen didn’t fit the archetype. He wasn’t dropping Kobe quotes. He wasn’t posting Instagram pictures of himself in the gym at 5 a.m. with the caption #RiseNGrind. He was different. He had different interests. He had different views. He thought about things in different ways.

"The intel coming out on him at the time was that he was this nerd who didn’t love basketball," one team executive told me.

The mistake wasn’t just the ignorance of conflating love and the ability to perform. It was failing to recognize that the very things Allen was being questioned about — the things that made him different — would turn out to be the very traits that one day allowed him to thrive.

*** ***

One night, toward the start of his rookie year with the Nets, not long after that combine interview, Allen shared a thought with Lamont King, his coach at St. Stephen's Episcopal High School in Austin.

"It would be pretty cool to make an All-Star team some day," Allen said. The two left it at that, but to King, it was clear that, having reached the NBA, Allen now had a new goal. He just wasn’t sure when he'd be in that conversation. But after three-plus solid years in Brooklyn, Allen was traded to the Cavaliers and is now playing the best basketball of his career.

When he and I spoke over Zoom, he was at the kitchen table of his Cleveland apartment, looking into the phone that he uses to follow Twitter updates from NASA’s Mars rover, Perseverance. Some leftover homemade sourdough bread — "It was my first time. It was OK, but I’m a perfectionist. My brioche buns are better." — was in the trash. Some home-built computers and a newly constructed LED Ping Pong ball clock sat in his bedroom.

"I’m just someone who’s really curious about things and always trying to expand my knowledge," Allen said when I asked about all his off-court interests.

It was an off-day in January when we spoke. The Cavs had lost to the Bulls the previous night, but they had reeled off five consecutive wins before that and would win another three in a row after our interview, propelling them into contention for the top spot in the Eastern Conference.

Yes, the Cleveland Cavaliers, in a season in which they don’t have LeBron James, are, as of this writing, 10 games over .500 and just two games out of first place. Their emergence is not just the most shocking development this season; it’s also one of the more shocking developments of any recent season.

There are many reasons behind the Cavs’ resurgence. Darius Garland’s breakout, rookie Evan Mobley’s dynamism, a lineup jelling and smashing opponents. But the 23-year-old Allen, fifth in the league in win shares, is at the center of the team’s success.

Allen’s strength is his ability to mix a selfless style with an elite package of versatile skills. Watch him navigate the court now, and you’ll see a player with a full understanding of how to impact winning by combining the most subtle of cerebral movements with elite physical tools.

He’s one of just 10 players in the league averaging more than 15 points (16.0) and 10 rebounds (10.7) per game. He’s second in the league in field-goal percentage (67.8%). No one is better at stepping up to set a perfectly timed screen, gliding to the rim and extending his outstretched "Inspector Gadget" arms (7-foot-5 wingspan) for a smooth and vicious slam.

He’s also the anchor of a suffocating Cavaliers defense (third in the league, as of Feb. 2). He blocks a good amount of shots (1.4 per game), but what he’s best at is remaining glued to his man for as long as possible and then sliding into driving lanes at just the right moment — again, arms extended high and/or wide — to contest or deter an opposing shot.

"He does everything," said Timberwolves guard D'Angelo Russell, who played two seasons with Allen in Brooklyn. "He covers everybody's mistakes by blocking everything, but if you want him to switch, he can guard the James Hardens of the world. On offense, you don’t run any plays for him, and then you look up, and he has a double-double.

"If I’m starting a team, he’s one of the first guys I choose just because of everything he can do. Yet at the same time, he doesn’t need anything."

Today, this seems obvious. Five years ago, it was considered by many to be a weakness.

*** ***

As a kid, Allen and his older brother played a ton of Super Smash Bros. Jarrett often lost.

Typically, this would be the point in the story where you hear about how furious those defeats left the future professional athlete. How he’d hurl his controller at the screen or storm off in a fit of rage or mope for weeks, the idea being that even at a young age, it was clear not just that this future pro felt the need to win but also how much he despised losing. That’s the sort of story the evaluators in that Chicago hotel room no doubt would have liked to hear.

Allen was a competitive kid, but for him, that competitiveness manifested in a different way.

"I was more of the ‘go back to my room later to practice’ type," he said. "I wouldn’t go straight to it. I wouldn’t be obsessed, but I’d spend a couple days playing on my own in single-player mode."

Allen grew up in Round Rock, Texas, the son of Leonard, a former San Diego Star and onetime Dallas Mavericks draft pick. His father, despite his background, didn’t push the sport. Most of Allen’s basketball experience came in pickup games at local churches and rec centers. He was allowed to develop interests outside of basketball. He’d go to museums with his mom. He built his first computer in high school.

By his sophomore year, he’d shot up to around 6-foot-9 and blossomed into a top prospect. He became goal-oriented, even writing things down. He was also more introspective than most high school stars. "He was the only kid I ever had who would come to me after a practice and be, like, ‘Coach, I didn’t have a good practice. I’ll be better tomorrow,’" King said. "He was just always looking to improve."

Allen led St. Stephen's to two state titles. Texas started recruiting him. But Allen was different from most of the kids the Longhorns targeted. He was a bit of an introvert. He told Smart it usually takes him a year-and-a-half to become comfortable around new people.

"He wasn’t into the stuff that we normally do," said Darren Horn, an assistant coach for Texas at the time. What Horn remembers most about recruiting Allen is inviting him to the Frank Erwin Center on the school’s Austin campus for a game, "and I look up at one point, and they’re playing ‘Jump on It,’ and he and his buddy are doing the dance and have the biggest smiles on their faces. He just loved it."

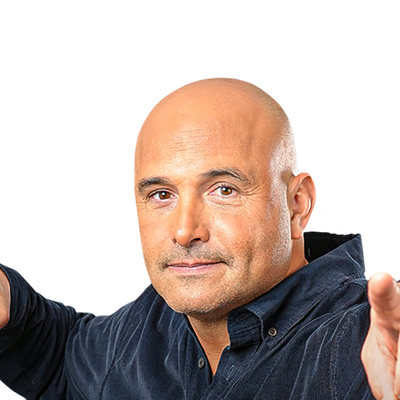

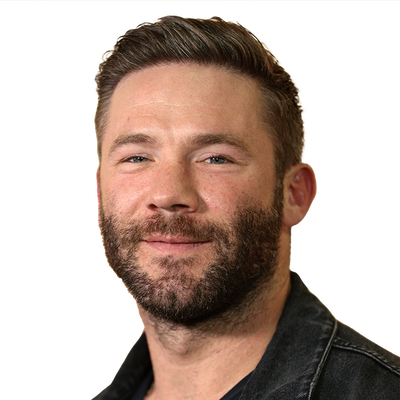

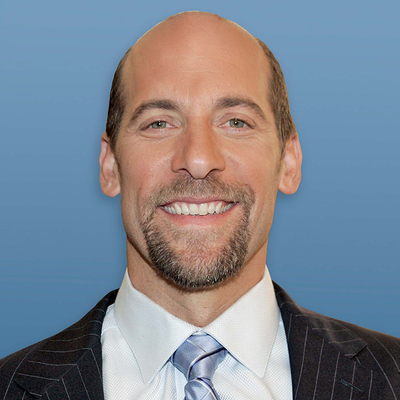

Allen averaged 13.4 points and 8.4 rebounds in his lone season as a Longhorn. (Photo by Chris Covatta/Getty Images)

Horn and Smart loved coaching Allen. They loved how competitive he’d get when they talked about some of the top players around the country. And how he responded when they challenged him during games. And how hard he worked. And how they could teach him how to read a double-team or show him how to spin baseline away from a defender, and he’d be able to apply it the next game.

"He has a real growth mindset," Smart said.

During my interview with Allen, I relayed this quote to him and asked where he thinks that comes from.

"Oh, from outside basketball," he replied. "I truly believe that."

*** ***

You know how this story usually goes. You’ve heard it dozens of times.

A player is invited to attend the draft. He hears a few names called before his. He starts to worry. Then another name is called. Then another. Then two more. Then three more. Then four more.

So. Many. Names.

Sitting there in the draft room, sleek suit feeling tighter, cameras panning toward his anxious face, the player stews. He’s angry. So, so angry. He’s better than all these guys. He knows it. How do they not know it? He vows to himself that he’ll show all of them. The coaches! The GMs! The media! The doubters! The haters!

Allen spent the 2017 NBA Draft in one of these situations. He was one of the final two prospects left in the invitee area of the Barclays Center floor. Then, finally, Adam Silver announced that the Nets were selecting him with the 22nd pick.

At that moment, there was just one thought flowing through Allen’s mind: "Not to trip on the stairs on my way up," he told me. "My brother had put that in my head, and I just kept going over it saying, ‘Don’t trip, don’t trip.’"

Which, OK, fine, is a bit different, but we can all understand how a gangly, 6-foot-10 teenager might be scared of such things.

But what about when you watch the clip of Silver calling Allen’s name and can see Allen respond by mumbling, "Finally"?

"That was more, like, the draft is really long," Allen said. "When you’re sitting there, those five minutes between picks really add up."

There was no outrage? Just boredom?

"I can't get angry at teams for not wanting to draft me," he replied. "I’m this 19-year-old kid, and these guys’ jobs are on the line. There's no hard feelings there. But I knew I had the ability to be in the NBA."

The Nets agreed. They had Allen ranked as one of the top eight players in the class. During a predraft meeting, general manager Sean Marks — a longtime San Antonio Spurs player, executive and coach — even pushed back at the notion of Allen’s outside interests prohibiting him from thriving in the NBA.

"People said the same thing about Tim Duncan," he told the room.

Allen was thrown into the Nets’ player development program, which at the time was the organization's priority. He needed the help. He was raw. He’d fumble passes. He’d travel once a game. Opponents had no problem dislodging his rail-thin frame.

"But he was so open to learning," said Bret Brielmaier, a former Nets assistant coach who was paired with Allen. "He had a deep desire to take his talents to the highest level possible."

Allen began peppering analytics coaches with strategy questions during games. He and Brielmaier started tossing a football around before workouts to improve Allen’s hands. The pair spent hours watching film — of Allen, but also of former greats. Karl Malone running the floor. Kareem altering shots. Even Duncan winning jump balls.

"We’d always bounce things like that off each other," Allen said. "Not even, like, super important, offensive things. But things like that stuff to try to improve my game in areas that aren’t on the stat sheet. When I came into the league, I didn’t know any of the nuances."

Allen was quiet in the locker room, but Nets players grew to love him. They appreciated how he didn’t care how many shots he took, that he was content screening and passing and passing and screening. They valued his willingness to cover for them on defense, even if meant being dunked on, which, in those earlier years, happened often.

"He’s one of my favorite teammates ever," Joe Harris said. "And when you get him out of his shell, he’s hilarious."

"He was different, but when you show up and do your thing, nobody cares," Russell said.

Early in Allen's Brooklyn tenure, his teammates also caught a glimpse of his fiery side. During a December 2017 matchup with the Miami Heat in Mexico City, Allen and Bam Adebayo, who had been drafted eight spots ahead of him, got tangled after a rebound.

Adebayo shoved Allen. Allen responded by jutting his face into Adebayo’s neck and talking trash.

"We were all like, ‘Holy s---, we didn’t know he had that in him,’" Harris said.

By the end of the 2020 season, Allen was averaging a double-double as the starting center for an upstart Nets squad. He’d become a premier rim protector and rim runner and helped Brooklyn snap a three-season playoff drought. He was confident in himself and his game.

Brielmaier told me a story about how, before a matchup with the 76ers, he was prepping Allen for his battle with Joel Embiid and asked Allen if he was ready.

"And he says to me, ‘He has to deal with me tonight,’" Brielmaier recalled. "And that was such a growth for him, understanding that he’s a really good player in this league and having that self-belief."

*** ***

In late September, around the start of training camp, Cavs head coach JB Bickerstaff called Allen, Mobley and Lauri Markkanen into his office. The Cavaliers had traded for Allen the previous January — as part of the three-team deal sending Harden to the Nets — then drafted the 6-foot-11 Mobley third overall, then given Allen a $100 million extension, then, a month after that, dealt for Markkanen, another 7-footer.

The players were confused. Why would a team in today’s guard-heavy league lock itself into a core featuring three near-7-footers? There was no way, they assumed, that there would be enough minutes and touches to go around.

That’s when Bickerstaff explained the plan for the season. "He told us that we're going to start doing this tall-ball lineup," Allen told me.

The meeting was quick. Five minutes, maybe 10. Bickerstaff ended with a request.

"He said he wanted us to start a group chat so that we could get to know each other and connect," Allen said. "We quickly learned that everybody is into their own business, and nobody likes reaching out much. So we stuck to real life."

Initially, it didn’t work. The Cavs dropped four of their first seven games. The offense was clunky. The trio couldn’t figure out how to mesh.

"We all kept trying to post up at the same time," Allen said. "Two of us were always guarded by a smaller guy, and we’d always go right to the post."

During film sessions, Bickerstaff would freeze the frame any time multiple players veered into the post. Little by little, the group began to jell. They started gaining a feel for one another on offense. On defense, they became impenetrable. By mid-December, the Cavs had climbed into the top half of the Eastern Conference standings. All the learning Allen had put in over the years was paying off.

He’s now strong enough to wall off bigs ("I’ve basically added seven-to-10 pounds every offseason," he said) and swift enough to roam the perimeter and check mobile wings. He started flashing fleet footwork and a nifty hook shot in the post. Brielmaier told me he has seen Allen toss more pinpoint passes out of pick-and-rolls than ever before.

"I just feel like things are clicking this year," Allen said. He told me he’s "talking in the locker room, making jokes with guys, going out to dinners and stuff like that" more frequently, too. "I just feel more comfortable than ever," he said.

With that comfort, he said, has come confidence. He had an example. Earlier this season, he found himself with the ball in the post with Portland Trail Blazers center Jusuf Nurkić on his back. Nurkić — at 7 feet and 290 pounds — is one of the biggest and strongest men in the league, exactly the sort of player against whom Allen used to struggle.

In years past, Allen likely would have tossed the ball back out to a guard. It’s unlikely he would have even established that position to begin with. This time, though, he decided to try something different. He took a couple of dribbles and spun to the right. Then he lofted the ball toward the hoop with his left hand. It splashed through the net.

He smiled while retelling this story.

"It was like, ‘OK, I can do this.’"

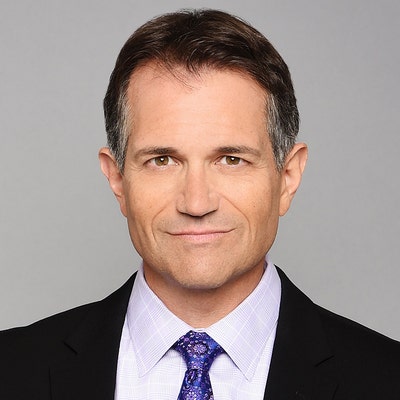

Yaron Weitzman is an NBA writer for FOX Sports and the author of "Tanking to the Top: The Philadelphia 76ers and the Most Audacious Process in the History of Professional Sports." Follow him on Twitter @YaronWeitzman.