We Lost 'The Game'

By RJ Young

FOX Sports college football reporter

Michigan-Ohio State.

Ohio State-Michigan.

This is where Buckeyes and Wolverines fans learn the meaning of tradition. This is where Buckeyes and Wolverines fans learn to define hatred.

This is their initiation, their rite and their resolve.

This is where rivalry becomes war.

This is where the game takes on new meaning, with the capitalization of those two words: The Game.

Tradition says mark this event – this pitch battle in the trenches of Ohio State Stadium in the even year, Michigan Stadium in the odd one – every third Saturday in November. But not this year.

This year, The Game is cancelled, which is one of the many ways we mark how the COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged our lives.

The Game was going to be played on the last week of the regular season – as has been its tradition since 1935 – on December 12. No. 4 Ohio State looked poised to run up the score, as a 30-point favorite, and stretch its winning streak in the rivalry to nine years.

While this year’s edition of the rivalry to end all rivalries did not have delicious trappings enjoyed often enough – of two Top 25 opponents engaged in a bitter battle for Big Ten (East) supremacy – a place in the College Football Playoff was part of the narrative.

The Buckeyes are off to a 5-0 start, but have had their backs against the wall, as the Playoff selection committee continues to search the Scarlet and Gray for flaws in a weak schedule that features just one Top 25 opponent. Ohio State would’ve loved the chance to bolster its résumé at the expense of who it calls "The Team Up North" — lest he be called traitor if a Buckeye says the word Michigan or even use an M in a sentence, aloud.

But after a 52-12 whipping of Michigan State despite being down 23 players, and without Buckeyes coach Ryan Day due to Big Ten-mandated COVID-19 protocol, only style points for the sake of showing off were to be had — from the outside.

From the inside, losing this game, The Game, is devastating.

Players mark their calendars for Ohio State and Michigan not by counting days to opening kickoff or the debut of the Playoff rankings or even Christmas. They count down the day they get to play Michigan, and each year, in the week leading in, The Game becomes all-consuming for players and coaches, alike.

Former Ohio State coach Urban Meyer treats the rivalry with reverence and has since he was a child. For him, it’s Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler. It’s a trip to the Rose Bowl on the line.

It’s a chance to claim a national title.

"And it was everything," Meyer told me this week. "I mean, it was 365 [days a year]. It was one of those things you talked about non-stop … And it was one of those things that just everybody talked about him. And I grew up in such Ohio State area. If you ever even thought about cheering for that other team, I mean, you had a fight on your hands."

Meyer came up in coaching as a grad assistant at Ohio State just a couple years after graduating from Cincinnati. After stops at six other programs – serving as head coach at three of them – over a 26-year career that includes three national titles, he earned the opportunity to coach the program of his boyhood in 2012.

Five years into his run as steward of Buckeye football, his No. 2-ranked Ohio State faced Jim Harbaugh’s No. 3 Michigan. It took four quarters and two overtimes for a winner to prevail in a contest with Big Ten title and College Football Playoff implications, and Meyer remembers it all.

Down 27-24, he remembered keeping the kicker on the bench and calling quarterback J.T. Barrett’s number for a 30th time on fourth-and-1 from the 16-yard-line. He remembered Barrett getting planted by UM safety Delano Hill and then inadvertently by OSU tight end A.J. Alexander at the line-to-gain.

"The place was so intense," Meyer said. "The Wolverines had the best defense arguably I’ve ever coached against in my career with Rashan Gary, Jabril Peppers and just a great player in [Chase] Winovich, and we struggled all day and went down there and tied the game with one second left to push it into overtime ... and I know the J.T. Barrett run that was really close on the spot."

The Spot.

Video review of the replay upheld the call, forever known as The Spot.

First down.

The 2016 edition of "The Game" is one of Urban Meyer's favorite memories at Ohio State, but Michigan fans will forever dispute The Spot.

"That was not a first down," said Harbaugh after the game, channeling ’73 Bo Schembechler. "I'm bitterly disappointed with the officiating today."

The next play Meyer’s offense ran would prove the difference. Buckeye wide out Curtis Samuel took a hand-off 15 yards to the end zone — touchdown. Meyer called the 2016 win one of his two favorite moments as OSU head coach.

The other? The No. 10-ranked Buckeyes’ 62-39 molly-whopping of Harbaugh’s No. 4-ranked Michigan. OSU quarterback Dwayne Haskins threw for 396 yards and six touchdowns in that game. Meyer still remembers the decibel level inside Ohio Stadium when the final whistle blew.

"I’ve never heard the stadium louder than in that moment," he said.

Being Ohio State head coach on the sideline in The Game remains one of proudest moments of Meyer's career. His seven-year stint in charge of the program is and will remain revered, as he never lost to Michigan.

That’s nearly twice as long as most players get to enjoy the rivalry, and, for the seniors, it’s even more special. It’s their chance to lead. It’s their chance to supplant a legacy, and the pandemic has robbed the 2020 class of its opportunity to record a moment in the only game that matters to them annually.

"My heart goes out to the seniors," Meyer said. "I mean, I'm absolutely devastated, heartbroken."

At the end of each edition of The Game during Meyer’s tenure, happiness was an emotion met with an equal amount of relief.

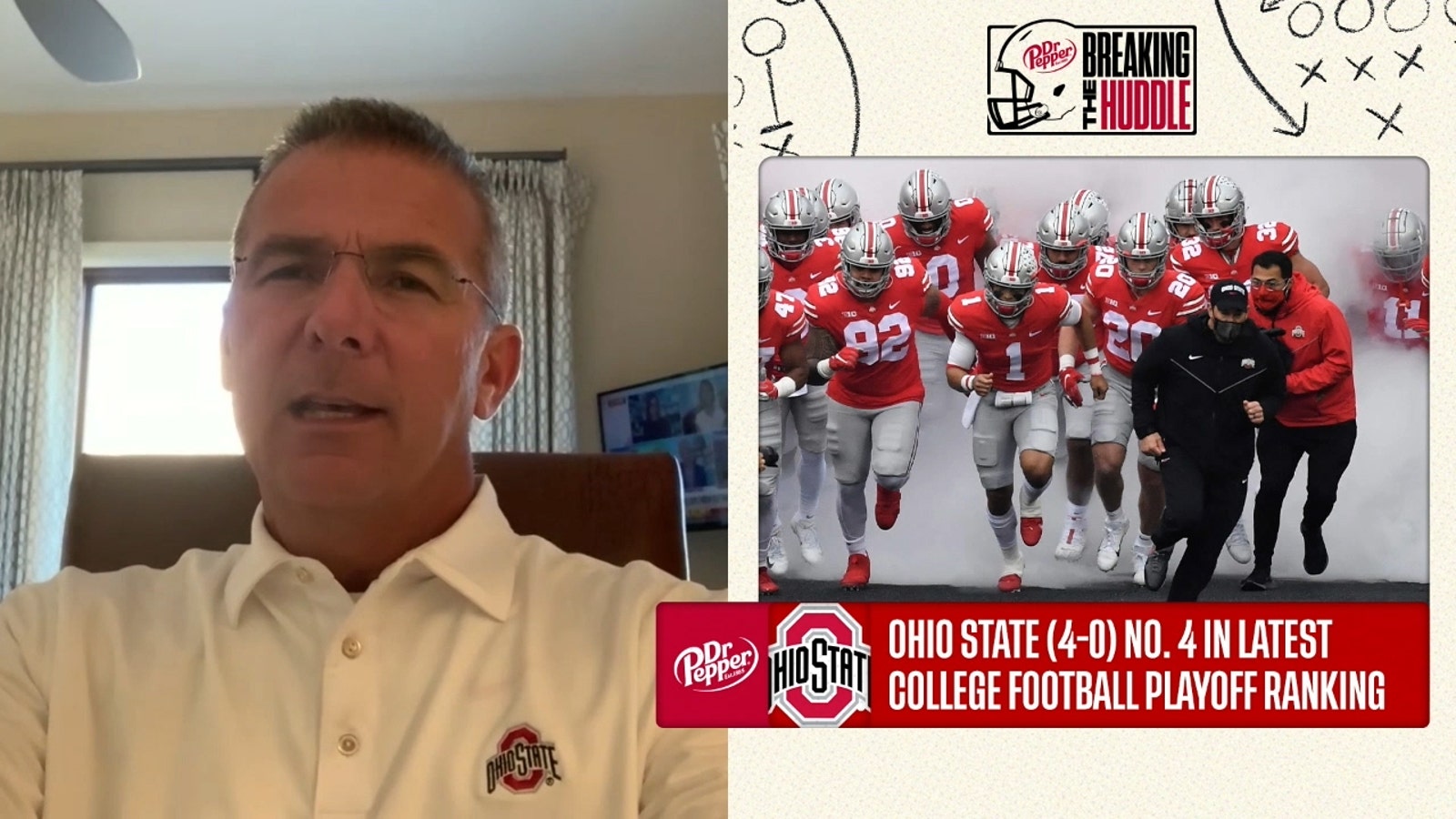

Urban Meyer on Ohio State’s case for the College Football Playoff

Meyer is analyst at FOX Sports and the Big Ten Network now, and he tried to explain to his colleague at BTN, Gerry DiNardo, what The Game means in the city of Columbus, in the state of Ohio, and across the country to the many acolytes of Ohio State football.

DiNardo – a former coach at Indiana, LSU and Vanderbilt – just didn’t get how much beating Michigan matters to the Buckeyes.

You could go 1-11 and beat the rival and it’s a good year?

"Absolutely," Meyer said. "You have to believe that if you're going to coach ... You ever stand up in front of a press conference at Ohio State and say that's not true, you might you might need some help getting out of that press conference."

Or even being welcomed back to your own home.

A HISTORICAL FEUD

Before becoming a three-time All-Pro linebacker and four-time Pro Bowler in the NFL, Chris Spielman was a two-time All-American at Ohio State. In 1987, he was named Ohio State Buckeye MVP.

He was born in Canton, Ohio, and raised in Massillon, Ohio. He seemed born to wear Buckeye colors. But he nearly went to Michigan.

Spielman was a heavily-recruited player in 1983. When he was named a high school All-American by USA Today, he was down to two schools: UM and OSU.

In "Michigan vs. Ohio State: The Rivalry," he related how he became a Buckeye.

"OK, where do you want to go?" his father asked.

"Dad, I want to go to Michigan."

"You traitor," father told son. "I'll tell you where you’re going. You’re going right down 71 South and you're going to play for the Ohio State Buckeyes."

Spielman’s father even doubled-down on his hatred for Michigan, knowing his son might defy his father. "Don’t ever come home if you do."

The Game predates the World Series by six years and the birth of the NFL by 23. The first game in the series was played in Ann Arbor, where Michigan battered Ohio State 34-0 in 1897.

Michigan fans will be quick to tell you that Ohio State didn’t win a game in the rivalry for the next 22 years. That Michigan, not Ohio State, is the winningest program in college football history and more than 40 wins ahead of the No. 2 Buckeyes on that list.

They’ll also remind you Michigan didn’t lose a game from 1901 to 1904. That by 1950, Michigan claimed eight national titles.

That the Wolverines had won 10 by the time Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947. That that’s two more national titles than Ohio State can claim in its entire history.

That a United States President, Gerald Ford, played football in their program. That in the 1950 Snow Bowl in Columbus, a game that produced 45 punts — several on first down — the Wolverines won 9-3 in perhaps the most memorable game of the series, and ended Wes Fesler’s career as Ohio State coach.

That the "Ten Year War" began with Ohio State getting its butt kicked 24-12 at the hands of the 1969 Michigan Wolverines. That it was Hayes, not Schembechler, who refused to cross the 50-yard-line to shake hands for a decade.

But Buckeye Archie Griffin’s proudest achievement on a football field isn’t winning two Heisman trophies. It’s winning three gold pants in the rivalry.

The pants are born of a phrase uttered by former OSU coach Francis Schmidt to inspire his players against a formidable Michigan club during his first season in 1934: "They put their pants on one leg at a time, same as everybody else."

The Buckeyes won the next game, too. And the next. And the next.

To commemorate each victory thereafter, Simon Lazarus and Herby Levy created the Gold Pants Club. They created gold pants lapels for each player on each Ohio State team that beat Michigan.

But it’s under Schembechler’s eye that Michigan became the team of Jim Harbaugh’s youth and where he learned to live as much by the creed of his father, Jack, and mother, Jackie, as he did the sign posted in Schembechler’s UM locker room.

"Those who stay will be champions."

RAISED TO BE A WOLVERINE

There’s a story Harbaugh told John U. Bacon for his book "Overtime: Jim Harbaugh and the Michigan Wolverines at the Crossroads of College Football." In it, Harbaugh tells on himself.

In his boundless will to affect outcomes he has no control over and yet still triumphs. Some might call that optimism — others, cockiness.

"Nobody in our family had ever been taller than six feet and I was determined to be the first," Harbaugh said. "I had my mind set on 6-2 as the goal and drank as much milk as I could possibly drink — and not that candy-ass 2-percent stuff, either! Whole milk!"

He took on the task of delivering milk to his class in school. He’d picked the cartons up to earn a free one and then he’d drink the milk from cartons leftover from kids who either didn’t want theirs that day or hadn’t shown up to school.

By middle school, Jim had grown to be as tall as his older brother John. By high school, Jim was 6-3 and the tallest member of his family.

At that time, he knew where he was going to play high school football. Hell, he knew when he was 12 years old and his father was an assistant on the Michigan staff. He was a quarterback, and a perfect fit for Schembechler.

"Quarterbacks are a special breed," Schembechler wrote in "Life, Laughs, and Lessons of a College Football Legend." "They need to be cocky, and the cockiest I ever had was probably Jim Harbaugh. You know how he got that way? By hanging around my practice field as a kid, waiting for his dad, Jack, to finish work … Even then, [he] was a devil, running on the field when he shouldn’t, playing with friends."

Jim did such a thing during the week of The Game in 1975. Schembechler hadn’t beaten Ohio State since 1971, and he was furious about this kid and his friends disrupting his practice in preparation for one of the biggest games of his career.

The way John tells the story, they were all playing a game of 3-on-3 when the ball was inadvertently tossed onto the practice field. John gave him a look like, 'You go get it. I’m not getting yelled at.'

And did Schembechler ever yell!

"Harbaugh! Get your damn kid off the field!"

Schembechler made a note in his book. "So, for the record, that is the youngest I ever yelled at one of my quarterbacks."

Later, when Schembechler saw Jim in a hallway, he asked an accusatory question. "You’re a cocky little guy, aren’t you?"

"Sometimes, I guess," Jim said.

A cocky guy who hates to lose.

When the Harbaughs lived in Iowa City, following Jack’s job, Jim earned his first chance to compete in a competition that mattered to him: Punt, Pass and Kick. At age 6, he won his age group.

Because big brother John didn’t, Jim traveled to the state finals with three other kids from the area. He aced the pass. He did well with the punt. But his kick — his kick just spiraled.

"It was sickening to watch," he said in Bacon’s book. "When they measured how far off center it was, and subtracted that from my distance, I might have had negative yardage. My punt and throw were good, but the kick killed me, and I didn’t win."

Two of the other kids he rode down with did win, and he found their celebrating with their trophies just to be a nauseating feeling. That feeling wasn’t jealously. It was losing. He’d lost.

"I’m in the backseat," he said, "on the left side, with the side of my face against the window, staring outside, just miserable as can be. And, no, I have not forgotten it!"

Anybody that believes Harbaugh wanted to duck this game – The Game – doesn’t get him. Doesn’t get how much being winless at 0-5 affects him.

Jim Harbaugh, right, grew up around Bo Schembechler's program and quarterbacked the Wolverines in 1983-86.

The man who asked special permission from the university to wear the Capital M hat on the sideline like Schembechler did doesn’t throw in towels. Doesn’t make excuses, and doesn’t seethe with humiliation at the thought of losing to the Buckeyes.

Yes, Michigan was forced to cancel the game because too many Wolverines were COVID-19 positive in the midst of Big Ten quarantine protocol. But he wanted this game.

With the NFL looming, and franchises looking hard at the man who could take a team to the Super Bowl but couldn’t win in Columbus, he does not want this to be his Michigan legacy. Now, he’ll have to decide whether this is the way it is, or if he wants to try to go at it again in 2021.

Will he stay? Will he be a champion?

In the meantime, the Big Ten is changing the rules to benefit their best team. And that best team is the Buckeyes.

Amid concern that the Buckeyes won’t be able to play in the Big Ten title game because they had not reached the previous threshold for eligibility of playing in six games, they conference is changing the rules. This is not the first time the Big Ten protected the Buckeyes.

In 1973, the Big Ten chose the Buckeyes to represent it in the Rose Bowl at Michigan’s expense. Both teams were 10-0-1 – with a 10-10 tie being the result of The Game – and tied atop the Big Ten standings.

After Michigan had scored 10 straight in the fourth quarter, Schembechler was incensed at the snub. "This is the darkest day of my athletic career."

Some will cry foul once again. As the Buckeyes, at best, will be a 6-0 Big Ten champion with the chance to play in the Playoff. But if they are, and do succeed in winning the national title, both will come with a caveat: The Buckeyes didn’t beat Michigan in 2020.

The Game wasn’t played.

RJ Young is a national college football reporter for FOX Sports. Follow him on Twitter at @RJ_Young. Subscribe to The RJ Young Show Podcast on YouTube. He does not like it when his socks get wet.