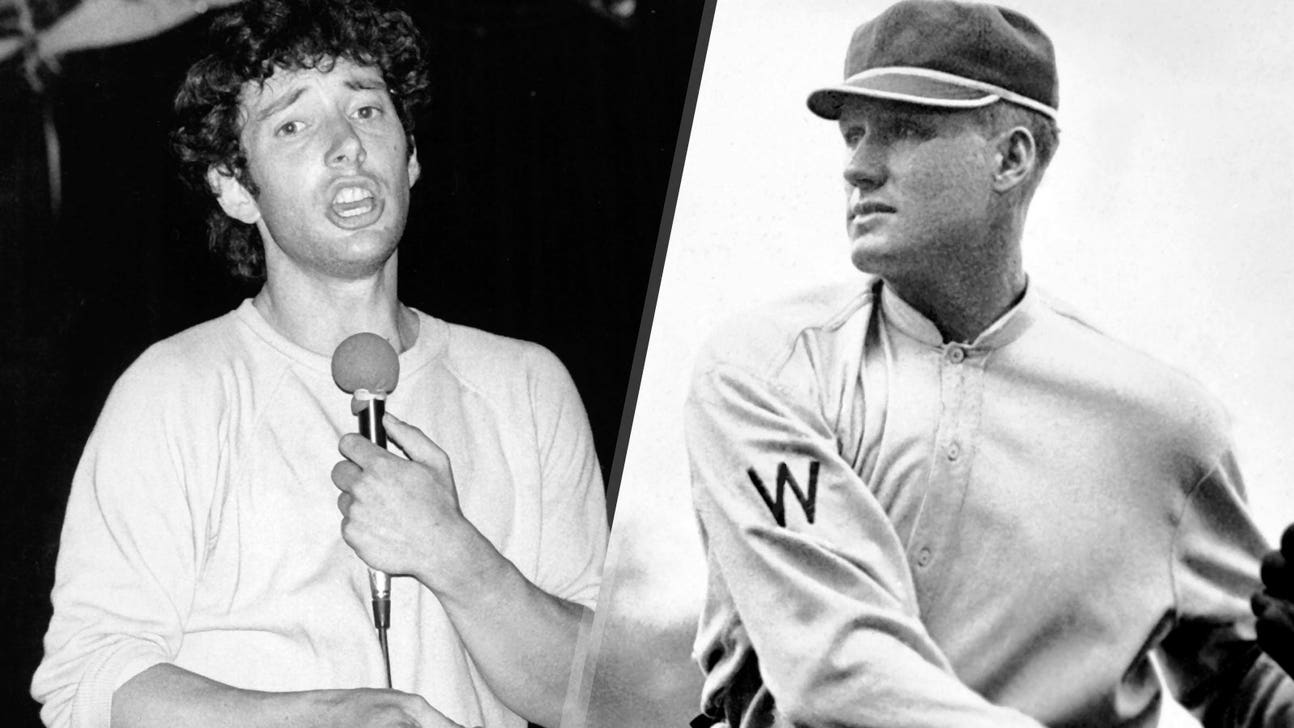

Bloop Hits: Jonathan Richman Rides the Big Train

From Jack O’Brien’s “Batterin’ Babe: Look at Him Now” to Warren Zevon’s “Bill Lee” and beyond, there’s a long and glorious tradition of songs about baseball heroes written by composers who were contemporaneous to their subjects.

In recent decades, however, we’ve seen songwriters digging increasingly into baseball’s past for inspiration, either out of nostalgia for earlier eras, or to celebrate a sense of connection with certain players that transcends the passage of decades. Dave Frishberg’s 1969 song “Van Lingle Mungo” was certainly among the first to mine this nostalgic vein, though it’s essentially just a list of retired players whose names Frishberg found particularly interesting or euphonious. But if I had to identify one song as being responsible for the late 20th/early 21st century trend of backwards-looking biographical baseball tunes, which extends from the S.F. Seals’ 1993 song “Dock Ellis” through to a substantial portion of The Baseball Project’s catalog, I’d nominate Jonathan Richman’s “Walter Johnson” ...

Recorded in 1985, nearly 58 years after “The Big Train” threw his last major league pitch, Richman’s song — which is sung largely a cappella, with only occasional guitar punctuation — praises Johnson’s good sportsmanship (though unmentioned in the song, Johnson’s other nicknames during his playing days included “The White Knight” and “The Gentle Johnson”) and his unwillingness to throw at opposing hitters. “Walter Johnson wouldn’t do that/Not even just a little,” Richman sings. “He made sure he threw the baseball/Right down the middle.”

This latter trait is, of course, a big part of the Big Train legend. In Lawrence Ritter’s landmark oral history The Glory of Their Times, Jimmy Austin claimed that the Washington Senators ace — whom he faced many times as a member of the New York Yankees and St. Louis Browns — was “too good a guy, scared stiff that he’d hit somebody” to come inside with his mighty fastball, while Johnson’s grandson and biographer Henry W. Thomas reported in his 1995 book, Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train, that the pitcher intentionally threw at a hitter on only one occasion, when (at the urging of his teammates) he dusted Frank “Home Run” Baker during a May 8, 1914 contest against the Philadelphia A’s. “I have only pitched one beanball in my life and I always regretted that,” Johnson later wrote of the Baker incident. “I made up my mind to never throw another.”

But while Johnson might not have ever taken intentional aim again at another hitter’s noggin, his gentlemanly ways clearly did not preclude the occasional inside smokeage. In 1915, a year after he’d sent Baker sprawling in the batter’s box, Johnson walked only 56 batters in 337 innings, which gave him a miniscule (and league-best) average of 1.5 bases on balls per nine innings pitched ... and yet he also plunked 19 of the men he faced, tying him for second-most in the majors. This dichotomy between low walk ratio and high HBP total occurred several times throughout Johnson’s career, including 1923, when he walked 73 hitters in 261 innings and only threw two wild pitches all season, yet also somehow managed to drill a career high of 20 opponents. Nice guy or no, you clearly dug in on the Big Train at your own peril.

Johnson, of course, isn’t the only historical figure to be saluted in song by Richman, who has written about real-life subjects ranging from Cleopatra and New York City stereo mogul “Crazy Eddie Antar” to artists Vincent Van Gogh and (most famously) Pablo Picasso, over the course of an eccentric but massively influential recording career that dates back to the early 1970s. “Walter Johnson” isn’t his only baseball song, either; it shares space on Richman and the Modern Lovers’ Rockin’ and Romance LP with “The Fenway,” a nostalgic song about childhood visits to the ballpark and other nearby attractions, which is itself a precursor to “As We Walk to Fenway Park in Boston Town,” which Richman wrote and recorded for the soundtrack to 2005’s Fever Pitch. But “Walter Johnson” feels like the most personal of any of those Richman songs, maybe because its lyrics seem to reflect Richman’s idealized vision of himself.

It’s no secret that we often feel a connection with certain ballplayers because we see (or would like to see) aspects of ourselves in them, or at least in the way that they play the game or comport themselves on the field. And since sincerity and an almost child-like sense of wonder have always been dominating characteristics of Richman’s songs, and it’s easy to understand why the author of such open-hearted, man-out-of-time statements as “Dignified and Old,” “Someone I Care About” and “My Love is a Flower Just Beginning to Bloom” might feel a kinship with a ballplayer who (in Richman’s words) “never so much as gave opposing team a dirty look” — even if said ballplayer retired nearly a quarter of a century before he was born, and even if (as with Johnson’s aversion to headhunting) such a charming attribute might be a trifle hyperbolized.

The last lines of the final verse really drive the Johnson-Richman connection home, though:

And a season’s just a season

In a game that’s just a game

And Walter Johnson cared about people

More than he cared about fame

Richman has never cared much about fame, either. His song “Roadrunner” may be of Boston’s greatest musical artifacts, and he’s enjoyed a few film appearances (Something About Mary and Fever Pitch), yet he’s managed to stay consistently true to his unabashedly humanist musical impulses while neatly sidestepping the pitfalls and temptations of life in the entertainment business. Johnson, who was certainly much more famous in his day than Richman ever was in his, nonetheless toiled in a similarly unrewarded fashion: he pitched in 802 games for the Senators from 1907-1927, yet only four of his Washington teams won 90 games or better in a season, and only one of them won a World Series. But as Richman sings, “Was there bitterness in Walter Johnson? Well, it was never detected.” To this day, bitterness continues to be relatively undetectable in Jonathan Richman, as well.