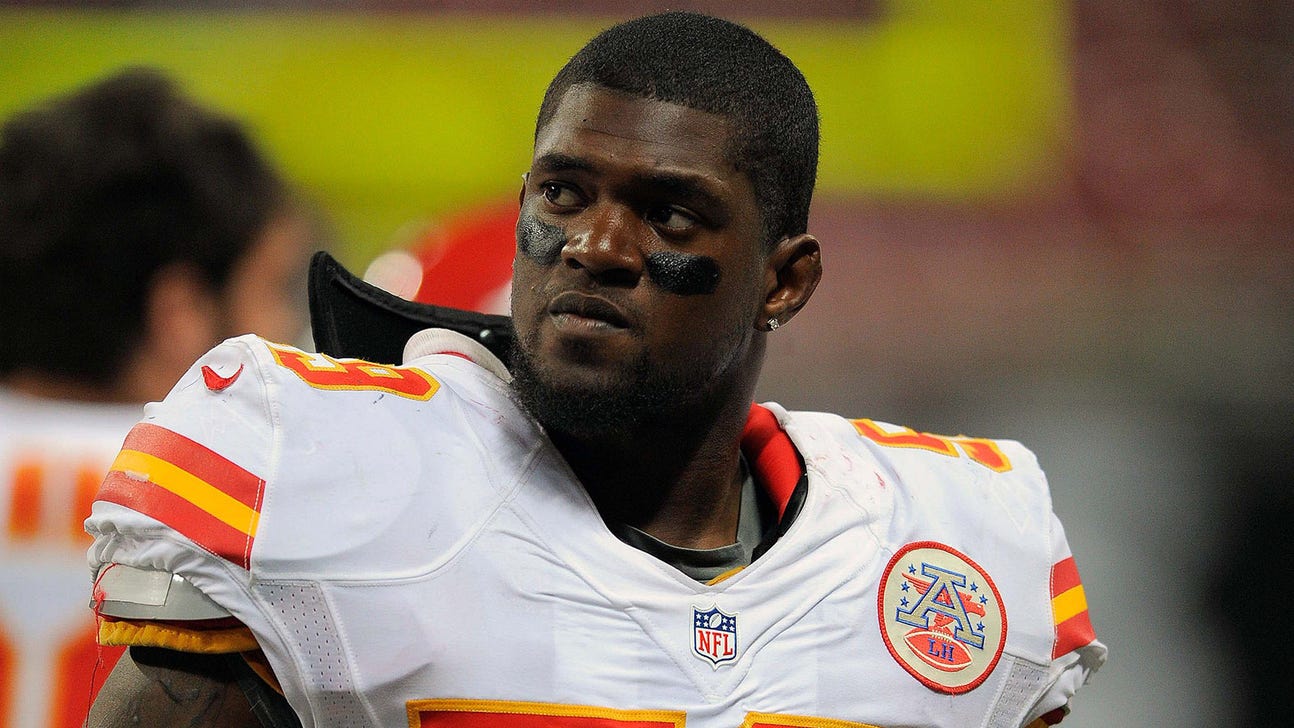

Did the Kansas City Chiefs make Jovan Belcher a monster -- or was the monster already there?

KANSAS CITY, Mo. -- As a freshman at the University of Maine, Jovan Belcher once put his hand through a window because of a woman.

On April 1, 2006, according to a report, the former Kansas City Chiefs linebacker "suffered a serious cut on his hand," the university police sergeant noted, after being "upset about a girl."

Less than a year after that, police at the University of Maine said a student called the cops on the late NFL linebacker because the "raised voices" of Belcher and a girlfriend during a "discussion outside his room."

There's more, of course, meticulously detailed in a story by the Bangor (Maine) Daily News dated December 3, 2012, two days after Belcher shot the mother of his child, Kasandra Perkins, then drove to the Chiefs' training facility and -- before an audience of coach Romeo Crennel and general manager Scott Pioli -- shot himself in the head.

As a collegian, Belcher took a for-credit peer education class in the fall of 2007 called "Male Athletes Against Violence." That last part has gotten quite a bit of traction, reporting-wise, over the last 13 months. Those first two incidents, not so much.

Sometimes, history elucidates. Sometimes, it revises.

The new narrative in the year since the Belcher tragedy is that of a talented, flawed, but giving young man driven to bouts of uncontrollable rage, alcohol binges and memory/concentration lapses because of either the stresses of an NFL life; workplace abuse; repeated concussions; or, more likely, some combination of three.

All of which may very well be true. The money is exorbitant; the stage, enormous; the pressures, massive; the contracts, not guaranteed. Gladiators or cattle, take your pick.

The question, of course, is whether it can be proven in a court of law. Because this much is on the record:

Jovan Belcher had a temper.

And, if you believe the Maine police reports, a violent one.

Now there must be context, too: In the aforementioned Bangor piece, Belcher's Black Bear teammates say any line crossed could well been blamed on alcohol or immaturity, accent on the former. Fair enough. Boys will be boys.

But when boys become men, and those men shoot a woman nine times and then turn the gun on themselves, and then that man's mother claims his former employer is responsible, all bets are off. And a young man's health records and incident history are fair game.

Did the Chiefs create a monster? Or did they just bring a rage that was already present but suppressed -- controlled -- out into the open?

And this, really, is Cheryl Shepherd's challenge. Shepherd, Belcher's mother, filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against the franchise late last month. In it, she alleges that he was subjected to "repetitive head trauma" and that the team didn't provide adequate medical care before the tragedy of December 1, 2012.

"Well, she has some hurdles ahead of her, no question about that," says Wichita-based employment attorney Alan Rupe. "It's going to be hard to do. But if she can do it anywhere in the country, she's in probably one of the best place to try, which is Missouri."

Last August, the NFL reached a $765-million settlement deal for more than 4,500 former players who developed dementia or other concussion-related health issues that they blamed on football. But because of a 2005 amendment to the workers' compensation statute in Missouri, employers within the state could be sued in civil court if the employees declined workers' comp; the window to file such suits closed on December 31. A group of 22 former Chiefs who played between 1987 and 1993, when the NFL did not have a collective bargaining agreement in place, are also seeking remedies from the club, claiming that the franchise hid the potential risks of lasting brain injury because of repeated head trauma.

Belcher's body was exhumed last month at his family's request so that his brain could be checked for chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a degenerative neurological condition. CTE has been linked to the deaths of former NFL stars such as linebacker Junior Seau, safety Dave Duerson and center Mike Webster. Shepherd is seeking a jury trial and judgment "in excess of $15,000 for actual damages, punitive damages, and/or aggravating circumstances, for the cost of this action, and for such relief as the court deems fair and reasonable.

"But the big hurdle to me is -- and I haven't done a whole lot of research on the science of head injuries -- but I've read enough to know that at best what they're (trying) to do now is show an association between head injuries and abnormal behavior," Rupe says of Sheperd's case. "But in civil tort law you've got to show causation, and that's more than just an association.

"You've got to prove to a level of liability that one causes the other. And I don't know that the science is refined enough now to say that everybody that has a head injury or concussion, that they're going to go and pull a gun out and shoot somebody nine times."

Reaction to Shepherd's suit has run the gamut in the court of public opinion, and understandably so. But whether you see this as a shameful money grab or a chance to pin nervous NFL officials where they don't want to be -- under oath -- hands are out.

Rupe, who's specialized in employment law since 1978, thinks this may very well go to trial if it "overcomes the workers' comp exclusion, which they might be able to."

Of course, Belcher was legally intoxicated the morning he pulled the trigger. Another hurdle.

"I think the best they can show is a high causation," Rupe says.

"And that is, is there evidence that a concussion is more probably true than not true (to) cause you to drink and cause you to flip out and pull out a gun and shoot somebody and then drive back to your place of employment and kill yourself? I think that's a big hurdle there. I think that's a fairly tenuous coupling of events to say one caused the other."

Gregory Leyh, a Gladstone, Mo., attorney who's working with Shepherd and Belcher's survivors, did not return a message seeking comment. Dr. Gary Namie, a social psychologist with the Workplace Bullying Institute in Bellingham, Wash., returned a call but declined comment.

"It's very difficult, I think, for individuals to understand some of the science because studies or individual reports of cases of these CTEs," UCLA neuroscientist Mayumi Prins tells FOXSportsKansasCity.com. "And we have to be careful about doing that. What really needs to happen is, we really need to see comprehensive studies ... to determine whether or not this is a cause-and-effect relationship."

It's not just about grey matter here -- it's about grey area. Shepherd's suit claims Belcher was knocked unconscious during a game against Jacksonville in 2009 but didn't receive adequate treatment prior to returning to team activities. It claims Chiefs officials berated and mentally abused her son, calling him "an accident."

And yet he reportedly thanked Crennel and told Pioli, "I love you, bro," before taking his own life.

"There are genetic pre-dispositions that many individuals have that may come into play as well," says Prins, an associate professor of neurosurgery at UCLA, director of education for the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center, and the co-author of a fall 2013 report which found concussion rates to be higher among high-school athletes than among their collegiate counterparts in some sports. "And there are some people who have concussions that may not lead to these (actions)."

Did the Chiefs light the fire, or fan the flames? A mother wants answers. Answers, a mother deserves. Accountability, a mother deserves.

A handout, she doesn't.

You can follow Sean Keeler on Twitter @seankeeler or email him at seanmkeeler@gmail.com.