Manchester United fans still bitter over Malcolm Glazer's role at Old Trafford

LONDON --

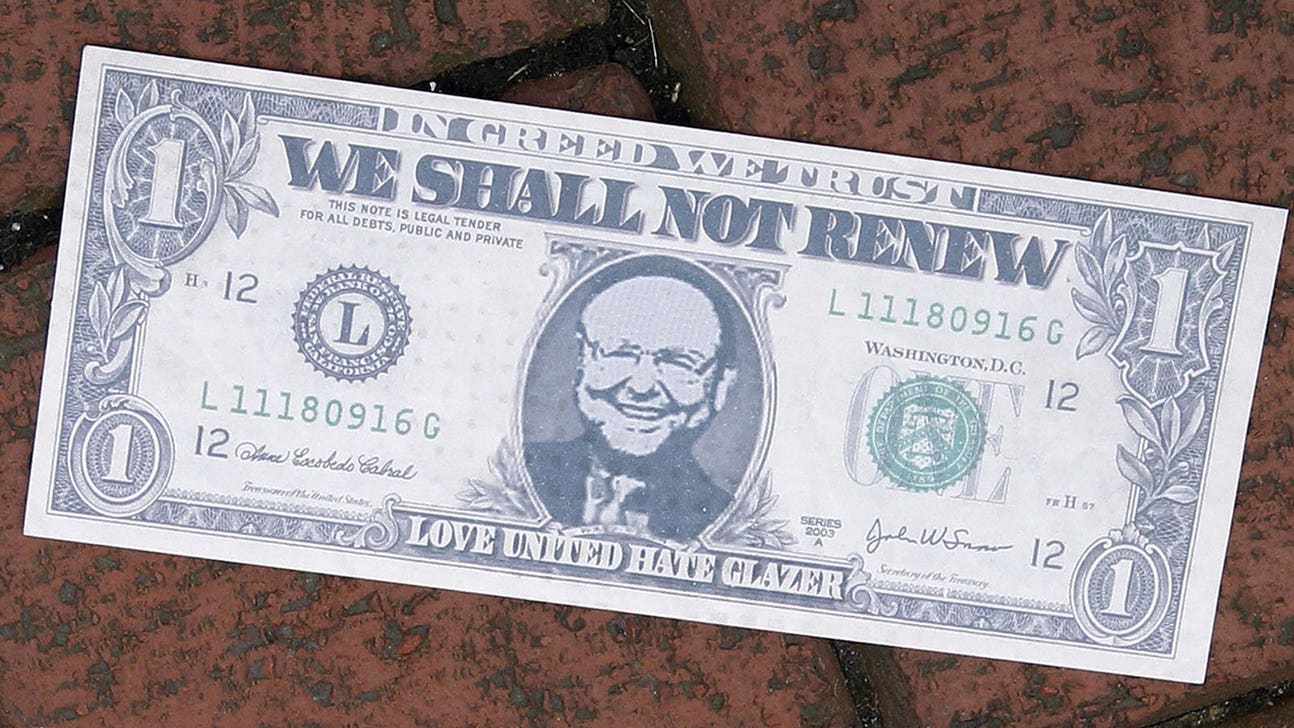

There were few tears shed in Manchester when the news of Malcolm Glazer's death broke on Wednesday. Even though he no longer held any shares in the club and was no longer on the board, his holding having been taken by his sons, Glazer had become a byword for what a section of fans see as the unwelcome ownership of English football. Even now, nine years after his takeover, a deal that introduced the notion of the leveraged buy-out into English football, the graffito can still be seen around Old Trafford: "Love United, Hate Glazer."

The issues with his family's takeover of United are twofold. On a general level, it was symptomatic of a general selling-out by English clubs to foreign owners -- and this was United. It wasn't a medium-sized club looking to better itself; it was the biggest club in England, the club that had best taken advantage of the possibilities of the new world of the Barclays Premier League and satellite television to become a financial juggernaut. If United could be sold, then the game had been sold. Of the 20 clubs in the Premier League last season, eleven had foreign owners.

The age when clubs were owned by a local businessman made good, when they could somehow be portrayed as expressions of local identity and pride were over and the Premier League had become a global league that happens to be based in England (and Wales). Many fans still feel uncomfortable about that. Manchester United fans in the United States or Malaysia or Nigeria may not care about that, but for those from Salford whose family had supported the club for generations, it was still a wrench. Of course plenty of local businessmen in charge of clubs have made plenty of mistakes -- some have acted criminally -- but it was easier to imagine a local owner, somebody who had perhaps stood on the terraces as a boy, might have the club's best interests at heart.

Nobody believes the Glazers have United's best interests at heart. They are there to make money and the best fans can hope is that there is congruence between their dividends and winning trophies. This past season, as United finished a distant seventh, its worst performance of the Premier League era, the doubts that already existed about that have been intensified.

From the outside, it's very difficult to know who is to blame for the fact United was left with an ageing defense and a stagnant midfield. David Moyes, as managers do, took the brunt of the criticism and was dismissed. Questions were asked too of the new chief executive, Ed Woodward, whose naivety in the transfer market was exposed last summer. But there were also those who pointed out how United's spending has fallen over the nine years of the Glazer ownership.

In 2005, United was a club that made a profit. It had cash reserves. Then the Glazers took it over, borrowing $893 million to do so and loading the debt onto the club. By January this year, according to the financial analyst, United fan and blogger Andy Green, the cost of that borrowing stood at $1.15 billion. For the financial year 2012-13, United spent $120 million servicing the debt in interest repayments and a premium for refinancing. Even with that $1.15 billion spend, the club remains $661 million in debt, although a number of recent sponsorship deals meant that they made a profit last year of $29 million after the interest repayments are taken into account.

Of course not all of that $1.15 billion would have been spent on players, but it's hard to avoid the conclusion that without those outgoings rather more may have been available. Sir Alex Ferguson always insisted money was available, yet the big deals United were accustomed to seal -- Ruud Van Nistelrooy for $32 million in 2001, Rio Ferdinand for $51 million in 2002 and Wayne Rooney for $34 million in 2005 to take just three examples -- dried up after the Glazer takeover. United fans opposed to the Glazers always point to the summer of 2009 when Cristiano Ronaldo was sold to Real Madrid for $137 million. United didnât pursue an interest in Carlos Tevez, for whom Manchester City paid his third-party owners $77 million. United that summer instead brought in Luis Antonio Valencia, Chris Smalling, Gabriel Obertan and Michael Owen for a total of $49 million.

Spending has begun to increase -- $45 million spent on Marouane Fellaini last summer and a further $60 million on Juan Mata in January, with talk of $250 million available to the new manager Louis van Gaal this summer. That will assuage some of the criticism, but the fact is that such a rush of signings is only necessary because of under-spending in the past. And, as Tottenham Hotspur found last summer, bringing in a number of expensive players in one bundle makes it harder for them to gel, sowing disharmony and creating instability. United can probably afford one season out of the Champions League; two seasons would be a lot harder to survive.

The fear is that protracted under-spending has created a long-term structural weakness from which it could take years to recover -- and if that happens, further anger will be directed at the Glazer family. Nine years after the takeover, there are still many United fans who believe that when Malcolm Glazer bought the club, he stole a little part of its soul.