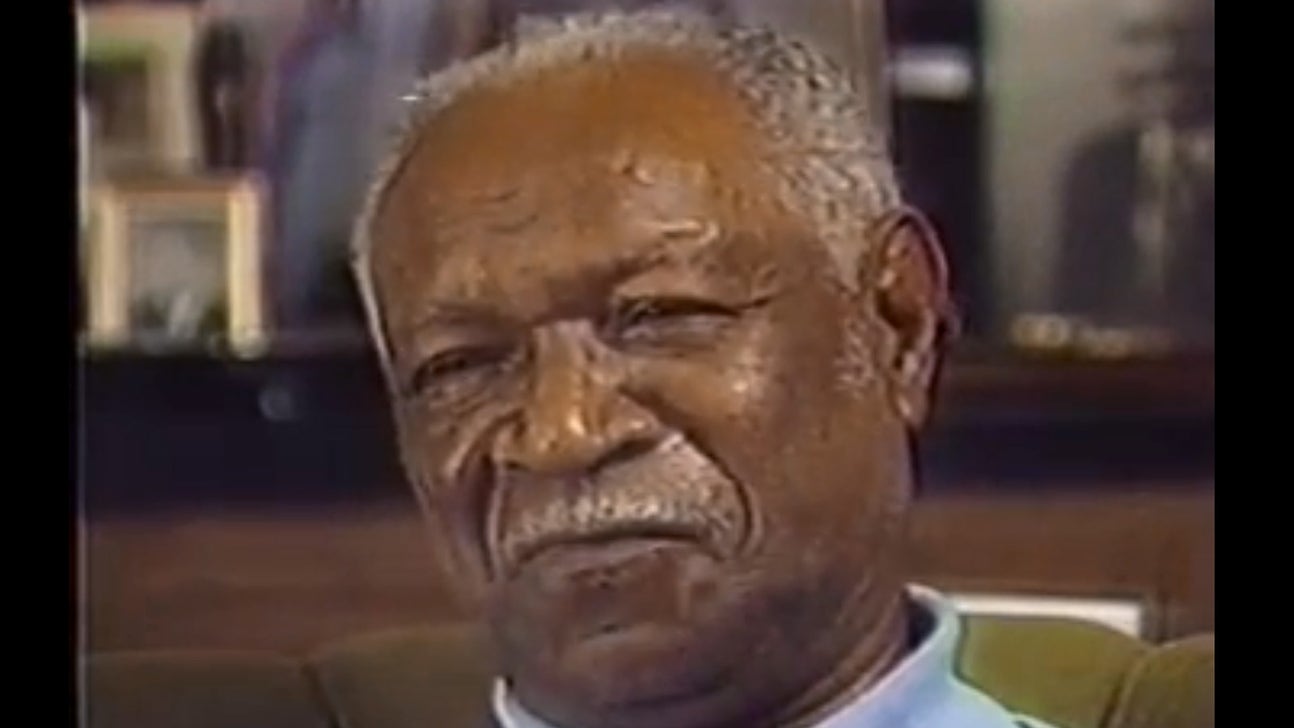

Jake Gaither rattled off winning seasons at Florida A&M

The son of a Baptist preacher from Tennessee, Jake Gaither was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps from a young age and embark on a career in church.

Fortunately for Gaither and Florida A&M University, the game of football found him first and allowed Gaither to go on to one of the most successful coaching careers in the history of the game.

In 25 years at the helm of the Rattlers program, Gaither won 204 games to just 36 losses and four ties and won six Black College National Championships. His teams had one or fewer losses in 15 of his seasons, and only former Mount Union coach Larry Kehres has a higher winning percentage among coaches with more than 200 victories.

Gaither also helped integrate football in the south, setting up the first meeting between a predominantly white school and a predominantly black school, and sent more than 40 players to the NFL in his time at FAMU, including Bob Hayes, Willie Galimore and longtime Bengals cornerback Ken Riley.

“He was someone that we all looked up to and respected because of the way he carried himself on and off the field,” Riley said of Gaither, who was known to call his players “my boys” and once famously said he liked his players to be “mobile, agile and hostile.”

“He didn’t have any children, so we were like his children,” Riley continued. “He was concerned with us not only as athletes, but as individuals. He constantly instilled in us the idea of, ‘What are you going to be doing 10 years from now?’ and he wanted us to be productive citizens.”

Gaither elevated Florida A&M to national prominence during a time of segregation and built an extensive network of former players and coaches that allowed him to bring some of Florida’s top recruits to Tallahassee. But that didn’t mean that FAMU was without competition on the field.

“These days, the best players go everywhere, but at that time, they went to FAMU,” Riley said. “At my high school, he didn’t even have to come get me. My coach basically just delivered me, hands on … but we played against some of the best talent because a lot of schools were still segregated at that time.

“You look at Walter Payton, he went to Jackson State; you look at a lot of guys from Grambling, you had Willie Brown, James Harris, Essex Johnson, Charlie Joiner; you go to Southern and you get Mel Blount. So we all played against each other.”

Perhaps the most notable of Gaither’s accomplishments came in his last year on the sidelines, when he took FAMU to Tampa for a game against the University of Tampa in his second-to-last game as the team’s head coach. The game, which FAMU won 34-28, is believed to be the first college football game between a black team and a white team in the south, and it went off without any issues.

“It didn’t matter who won,” Gaither said at the time. “Either team could have won, but it was the first interracial game in the south and I was of the impression that such a game could be played without any undesirable incidents developing.

“There were 47,000 people attending and not one incident of a racial nature on the field or in the stadium or in the city of Tampa that night. That proved to me it could be done in the south. That’s the most satisfying game I’ve had.”

Said Riley: “It’s amazing how people will come together for sports, but can’t do it in the real world.”

Gaither’s efforts at FAMU didn’t go unnoticed by fellow members of the coaching fraternity, and some of the biggest names in coaching — from Woody Hayes to Bear Bryant — were regulars at Gaither’s annual coaching clinic at the school. Gaither was inducted to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1975 and was remembered fondly after his death in 1994 at the age of 90. But for former players like Riley, it’s important to make sure his legacy continues to live on.

“He was well respected and loved and he never raised his voice — he had that baritone voice — and the way he carried himself on and off the field, you could sense that he was concerned for you as more than just an athlete,” Riley said. “As time slowly passes, people will eventually forget you, and it’s a shame that some of these great athletes and people and humanitarians are forgotten so quickly and are overshadowed by what’s new.”