Some years ago, I learned that Charles “Victory” Faust was buried just south of Tacoma. As it happened, my travels since have routinely taken me within a few miles of Charlie Faust’s resting place. When I took the train to and from Seattle, I would gaze to the East and think about Faust; when I drove, I would gaze to the West.

Finally, last weekend I made a little arrangement with my ever-tolerant wife.

Alas, my ever-tolerant wife wasn’t feeling well, so she stayed in the car. I grabbed the infant from her plastically indestructible seat, and off we went in search of Charlie Faust, or what’s left of him anyway.

I’ve made a habit of this, over the years, going to see the monuments to baseball stars. And Charlie Faust might be the oddest, unlikeliest star in baseball history, if not the history of American professional sports.

I first came upon Charlie Faust 30-odd years ago, the first time I read Larry Ritter’s seminal book, The Glory of Their Times. The book, a collection of (brilliantly edited) interviews of players from baseball’s Dead Ball Era, included a chapter on New York Giants outfielder Fred Snodgrass, who told the most incredible story about a fellow from Kansas named Charlie Faust who showed up one day, and told manager John McGraw a fortuneteller had told him he would pitch the Giants to a championship.

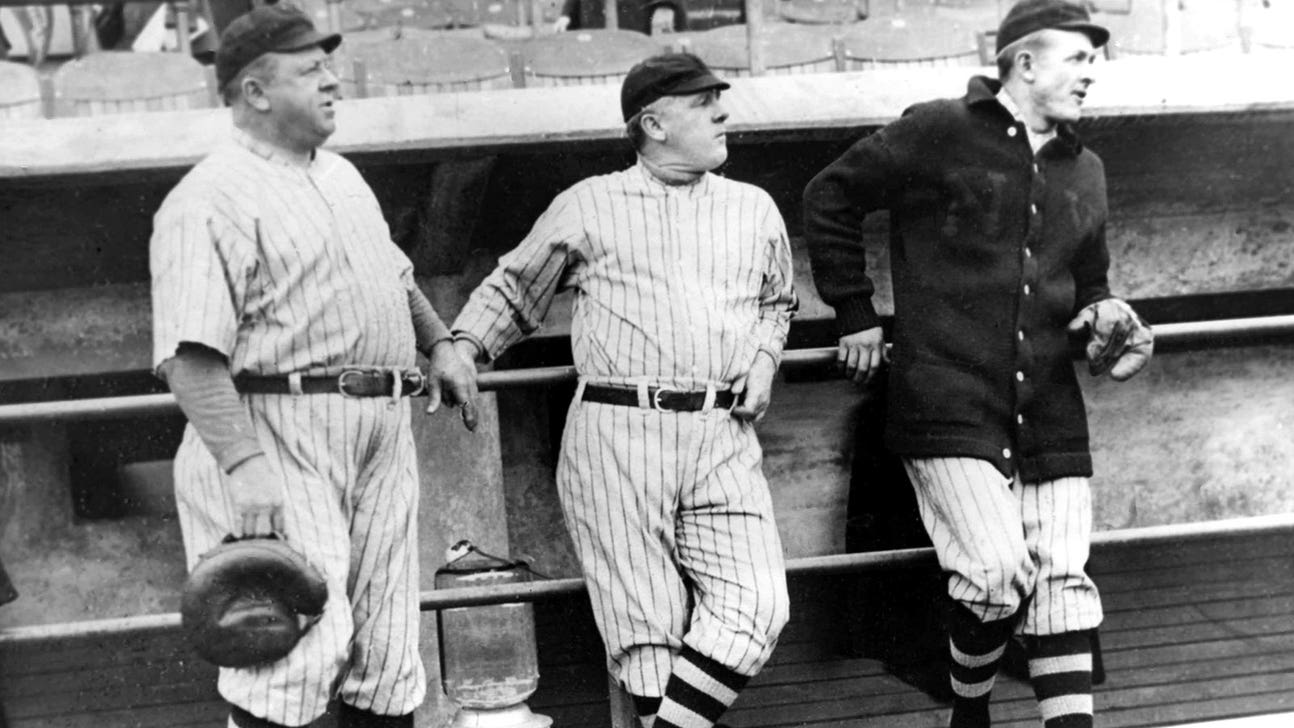

Of course McGraw thought Faust was a kook, but the players (and the many New York writers!) got a kick out of Faust, so he was allowed to hang around the club for a while.

And pitch in a couple of actual games that counted.

And damn if that fortuneteller wasn’t almost right. According to Faust’s biographer, “From the time [Faust] met McGraw in St. Louis to the day the Giants clinched the pennant, the team had a record of 39-9. When he was in uniform and exerting his jinxing powers, their record was an astonishing 36-2.”

The Giants’ luck ran out in the World Series against the Athletics, and the next spring Faust was back ... but this time with the Dodgers, for whom he pitched an entire exhibition game in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Faust would rejoin the Giants when the real season began ... and again they couldn’t lose, opening the season with an astounding 54-11 record. Still, McGraw (again) grew tired of Faust, who was finally convinced to return home to Kansas, from where he would (the Giants told him) be summoned when needed.

The Giants won the pennant again, and lost the World Series again. Meanwhile, the summons would never come. So Faust “peppered McGraw and the National League office with requests for reinstatement on the team, with back pay for his contributions to their pennants.” That worked as well as you might guess. Meanwhile, Faust moved to California and then Seattle, where he joined his brother. In 1914, he attempted to rejoin the Giants, an effort bound to fail when Faust walked from Seattle to Portland, where he was found on the streets in a daze, and shipped to the state’s mental hospital in Salem; on his admission form, Faust listed his profession as “professional ballplayer.” Diagnosed with dementia, after seven weeks Faust was sent back to his brother in Seattle. But before long he was back in the hospital, this time the Western State Hospital just of south of Tacoma. And in June of 1915, he died there of tuberculosis.

For many decades, Charlie Faust and hundreds of other patients who died in that era were buried across the road from the hospital, with only cement numbers marking their resting spots. Until 2004, there was actually a state law requiring the anonymity of everyone laid to rest there. But some do-gooders got the law changed, and now proper markers with names and dates accompany most (but hardly all) of those old cement blocks.

The Western State Hospital’s cemetery used to be in the middle of a huge field, but now it’s surrounded by a dog park and softball fields and soccer fields. There’s a map of plots – no names, but numbers; and I had Charlie Faust’s number – just inside the gate; alas, I walked right past the map, which meant a lot of extra walking around with the infant slung on my hip. Still, the sun was out and there are worse ways to while away a Sunday afternoon. And after at least half an hour and a couple of false trails and plenty of retraced steps, we found what’s left of Charles Victor Faust.

In this cemetery, Charlie is sui generis. Everybody else has one of those old numbered markers, and most also have one of the new monuments. Only Charlie has a small, shiny aluminum marker with his birth and death dates (rather than just years); only Charlie’s grave shows evidence of visitation, with four nickels resting atop his numbered marker. We may safely assume, I think, that I’m not the first Glory of their Times devotee who’s been here.

Why do I visit these spots? It’s not to communicate with spirits. But I’ve never seen exactly the same thing at a famous player’s final destination, and the differences, paradoxically enough, never fail to illuminate the human condition. When the grave of a Hall of Fame player like Zack Wheat, for years the toast of Brooklyn, can wind up little-seen or -maintained, even in the middle of a major American city, what does that say about the fates that await we mere mortals? And what of Charlie Faust, for a few months the toast of Manhattan? If he can wind up here, surrounded by rambunctious canines and their oblivious masters, what guarantees might be found for the rest of us?

**************

If you’ve read this far, I’m grateful. It’s not often that a big-time website publishes a story about a long-forgotten and -neglected grave, for the simple reason that the subject has limited appeal. So I’m grateful to you for reading, and I’m grateful to my employers for allowing me to publish nearly whatever I’ve liked here.

I’m also grateful to everyone who’s written for this site, including my co-conspirators Ken Rosenthal, Jon Paul Morosi, C.J. Nitkowski, Gabe Kapler, and Steve Hofstetter, not to mention contributors Alex Goot, Anna McDonald, Ben Mankiewicz, Bob Klapisch, Cee Angi, Dan Epstein, David Golebiewski, Erik Malinowski, Jeff Katz, John Baker, Josh Wilker, Owen King, and Meg Rowley, and of course our many friends and collaborators at FanGraphs and Baseball Prospectus. I just wish I’d been able to find more readers for all of them.

Oh, and I should mention Jeff Garlin, who never actually wrote for this site but did give me one really enjoyable hour at the Hollywood Farmers’ Market a couple of years ago.

I'm pleased to nominate Charlie Faust for the Wing of Amazing, where he would join (in my mind) luminaries like Bo Jackson and Jamie Moyer. But I'm sorry to report that this is the last JABO post. In the near term, I’ll still be writing occasionally for FOXSports.com’s MLB page. In the long term ... hey, who in hell knows? Life’s short, but somehow we’re living longer and longer all the time.