Former Negro League star Binga honored, remembered with grave marker

MINNEAPOLIS -- Pacing through the grass at Crystal Lake cemetery, Pete Gorton kept one eye peeled for a clue, the other on his 1 1/2-year old daughter as she rested in his arms or crawled on the lush ground beside him.

Finding a particular headstone is one thing. Locating a grave without one is another.

Eventually, Gorton -- an avid baseball historian and, during the day, a communications specialist at a Twin Cities law firm -- found the spot. A nondescript patch of grass underneath which rested the body of a man who starred in his sport but never reached its highest echelon.

The man inside the coffin underneath Gorton and his daughter France's feet had been mostly forgotten.

But the past is not completely gone.

***

William Binga could rake with the best of them. The Michigan native batted above .280 in a dead-ball era when home runs were a rarity. Despite playing without a glove for close to half his career, he was regarded as one of the most effective fielding third baseman of his time. In one game, he cleanly collected 18 balls hit his direction.

But Binga's talents never took him past the sandlot-type fields of lower-level baseball and rural Minnesota "town ball," as it's come to be known. It never brought him much stability, either.

It wasn't for lack of ability. It was because William Binga was black.

The son of slaves that had fled the plantations of Kentucky, Binga showcased his arm and bat during a time when America and its self-proclaimed pastime were definitively and unmitigatedly segregated. Possible big-league talent was confined to the Negro Leagues, which Binga ransacked while bouncing from club to club from 1890-1926.

"The historical situation that he was in in terms of the color barrier and his inability to build a lasting legacy -- it was taken away from him," said Gorton, founder of the Donaldson Network, which along with a handful of constituent organizations tries to honor the memories of long-forgotten Negro League players. "He should've been in major-league circles and would've had the opportunity to do that had they not decided to this arbitrary thing."

The Page Fence Giants, sponsored by an actual fencing company. The St. Paul Colored Gophers. The Minneapolis Keystones. These were the teams Binga called his own.

Like many players of his day, he eventually settled in Minnesota, where manifold semipro organizations offered a chance to keep playing and earn a small paycheck. Binga's final baseball season, 1926, was spent playing for Willmar's town team.

The Klu Klux Klan was still active in Minnesota during that era. In 1920, three black circus workers were lynched in Duluth.

But that didn't stop Binga and the troupes of black baseball players that used to barnstorm throughout the state.

"He was considered a 'major leaguer,'" said Todd Peterson, the author of a book called "Early Black Baseball in Minnesota." "That was sort of code that he'd only be in the major leagues if it wasn't for his color. That was a line they used a lot. They used that about him."

After playing into his 40s, Binga hung up his cleats and tattered leather glove. On Oct. 14, 1950, he died in Minneapolis.

He was interred in Crystal Lake Cemetery,

And because he spent the final years of his life in abject poverty, nothing but blades of grass marked Binga's burial site.

Until last Saturday.

***

Some Generation Xers memorize their favorite rock band's discography as a hobby. Others spend their spare time watching old '80s sitcoms and reminiscing about the pop culture of their formative years.

But Gorton's pride-and-joy activity for years has been digging up research on John Donaldson. In 2008, Gorton helped oversee a grave marker ceremony for the former Negro League pitcher who recorded more than 5,000 strikeouts during a 30-year career.

Like Binga, Donaldson never got to play in the majors. Like Binga, Donaldson was buried without a headstone.

So, after years of excavating facts about his favorite player, Gorton helped identify Donaldson's Alsip, Ill., grave site and procure a marker to officially recognize it. He also created the Donaldson Network, which works with the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker project and a handful of other organizations to do the same thing all around the United States.

Donaldson and two other deceased Negro League players were the first to have their previously unmarked burial sites enshrined. Including Binga, the endeavor has honored about 25 African-American players and has a gargantuan list still left to tackle, Gorton said.

"I think it's important that the people of Minnesota and the people of the upper Midwest realize that, because of segregation, these guys were in their neighborhoods," Gorton said. "William Binga played in hundreds of towns in the upper Midwest. People knew who he was."

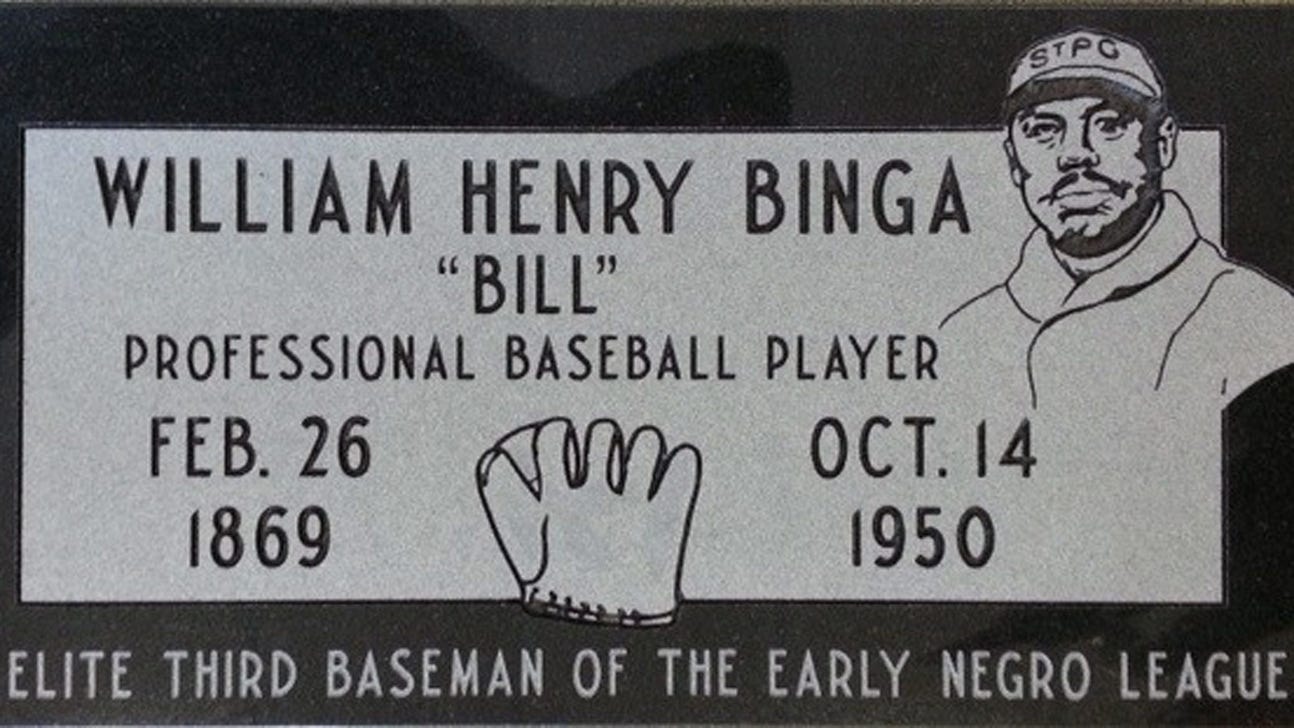

So Gorton joined Peterson and representatives from the Minnesota Twins and the Society of American Baseball Researchers on Saturday to unveil Binga's headstone, complete with a caricature of him in his St. Paul Colored Gophers uniform and the epitaph "an elite third baseman of the early Negro Leagues."

Gorton's wife and children, including Frances, who's been walking for years, were there.

"I had to do this," Gorton said. "It's our responsibility to find out who these guys were and to do our best job to try to help rebuild their lasting legacy."

***

When Jackie Robinson swung through Major League Baseball's color line in 1947, Binga was spending the final years of his life in Willmar.

Robinson became a face of dethroning segregation in baseball and in the United States. But there are many anonymous contributors buried in the ground today, mostly forgotten with not so much as a piece of rock to commemorate their lives.

But if Binga, Donaldson and their Negro League brethren don't play, Robinson doesn't have an avenue to the big leagues. And if Robinson hadn't courageously braved the masses at ballparks around America, a great step in the country's civil rights history would've been lost, too.

It's why Saturday's ceremony at Crystal Lake Cemetery went beyond remembering the career of a star athlete, said Twins director of diversity marketing Miguel Ramos, who also chipped in toward the Binga grave marker project.

"We're people. We're human. I believe we came from the same God," said Ramos, himself a Puerto Rican who immigrated to the U.S. about 20 years ago. "This isn't about baseball. It's about people."