NFL, union look to enforce equipment rules

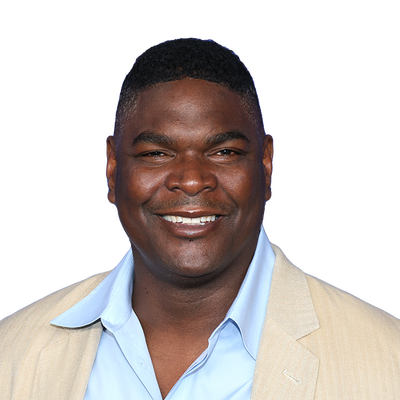

To the casual observer, Chris Cooley is dressed for success on game days.

The Washington Redskins tight end dons the standard NFL uniform with a helmet and shoulder pads. But upon closer examination, Cooley isn’t wearing any padding to protect his thighs or tailbone. And if he had his way, Cooley would shed even more of the equipment intended to shield him from injury.

“You just feel more comfortable, faster and there’s less stuff to move around in,” Cooley said last month after a Redskins minicamp practice.

Cooley isn’t the only one who feels this way. Only 50 percent of players wear every major piece of protective padding at their disposal, according to statistics given the league by the NFL Players Association.

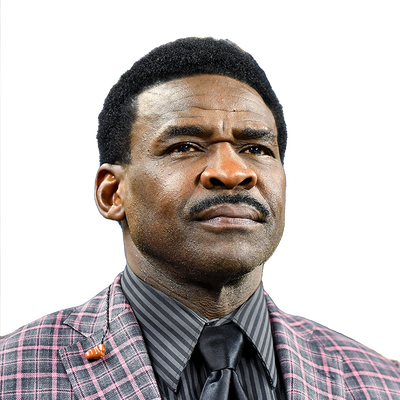

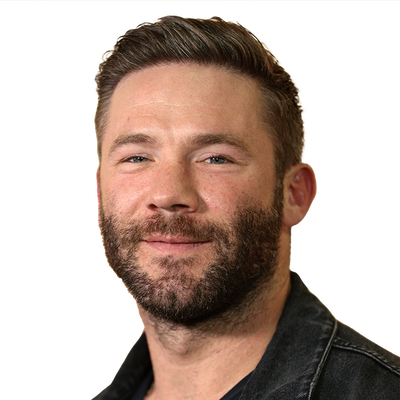

Even though it may lower concussion risk, one quarterback (Seattle’s Matt Hasselbeck) and two centers (Kansas City’s Casey Wiegmann and Washington’s Casey Rabach) surveyed by FOXSports.com said they don’t use mouth guards largely because of verbal communication concerns and discomfort. Wide receivers and defensive backs are known for eschewing any protection between their knees and torso. Some remove the actual padding and use only the thin plastic shells.

“I just don’t understand it,” Redskins defensive end Phillip Daniels said. “I’m an old-school guy. I don’t feel comfortable when I don’t have anything down there.

“This ain’t basketball. It’s football. Those pads are for a purpose.”

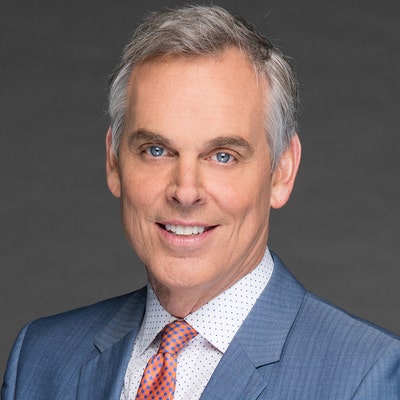

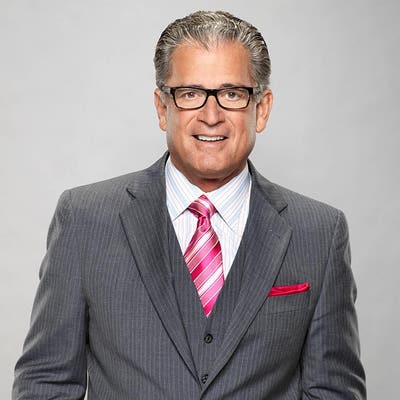

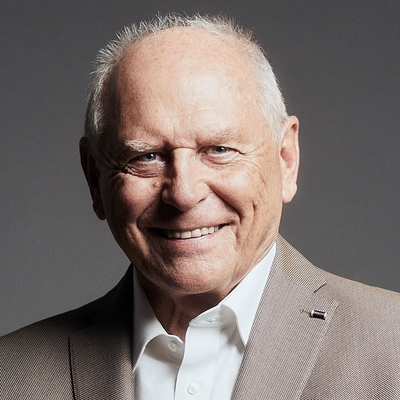

NFL commissioner Roger Goodell and NFLPA executive director DeMaurice Smith agree. Both told FOXSports.com last month they are working to craft rules that would make the use of more protective padding mandatory starting with the 2011 season. Smith said he is soliciting input from the NFLPA’s medical staff and current players about potential changes and how position-specific the required padding should be.

Ray Anderson, the NFL’s executive vice president of football operations, said the rules could be enforced by referees who would bar a player without mandatory padding from the field for repeat offenses (a similar rule already exists mandating helmet chinstraps are buckled). Game-day monitors whose main job now is checking that uniforms conform to league standards also would have expanded roles in pregame and halftime enforcement.

“From a players’ side, our job is to continually push for the safest working environment,” Smith said.

“That’s important not only on the field but, as we now know, critically important for what their lives can be like after football.”

In 1995, the league lifted the mandate for all padding except helmets and shoulder pads. Teams, though, can fine players who miss games or practices because of contusions suffered while not wearing pads.

Goodell admitted there is no “reliable data” that proves the injury rate would be lowered through mandatory use of pads or even mouth guards. The league has failed to track whether man hours missed from contusions or other injuries in prior seasons correlated with players who weren’t wearing pads. The NFL will start compiling such information this season.

“Whatever (the NFL) did back then under different leadership is what they did,” Anderson said. “But under this commissioner and his senior leadership, player safety is a priority -- period. If we don’t have players healthy on Sunday to play or practice during the week, nobody’s benefitting.”

Yet any changes would be met with significant resistance from those players who already feel they’re forced to wear too much equipment while also having to follow other league uniform requirements like socks pulled knee-high and tucked-in jerseys.

Vanity plays a major role in such thinking, especially among some wideouts and cornerbacks who are self-conscious about their appearances. Some also believe they run faster without pads, even though the NFL says such a contention has never been proven.

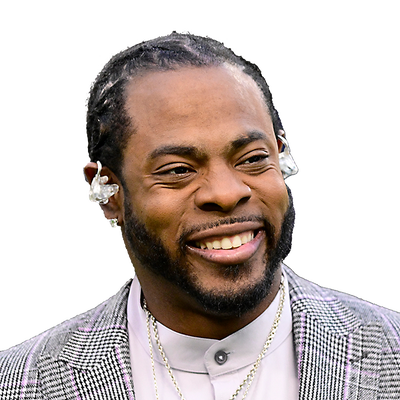

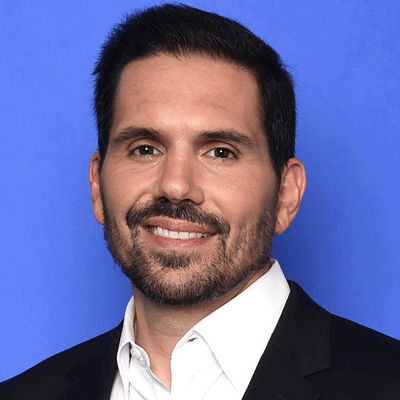

“It’s a combination of speed and looks,” said Chiefs wide receiver Chris Chambers, who uses shells to protect his thighs and doesn’t wear a tailbone pad. “It might be looks first, to tell you the truth. If you look good, you’re going to feel good. You’re going to feel fresh. You’re going to feel fast. You don’t want these big, bulky thigh and knee pads.”

The NFL is trying to address the problem through the introduction of new eye-catching protective equipment. Twelve teams during the preseason will experiment with an undergarment that has sewn-in pockets for sleeker thigh, knee and tailbone pads.

Yet to players like Cooley and Chambers, such steps are unnecessary. Veterans of six and nine NFL seasons respectively, neither has suffered a thigh or tailbone injury during their NFL careers despite a lack of padding.

“It’s not an area I feel needs protection all the time,” Cooley said. “I’ve never worn a (tailbone) protector. It’s not a necessary piece of equipment. It comes down to comfort and necessity of what I need at my position – where I’m getting tackled and hit the most often.”

Hasselbeck said he wears thigh and knee pads but wonders if they’re “just for looks. I don’t know if they’re doing anything.”

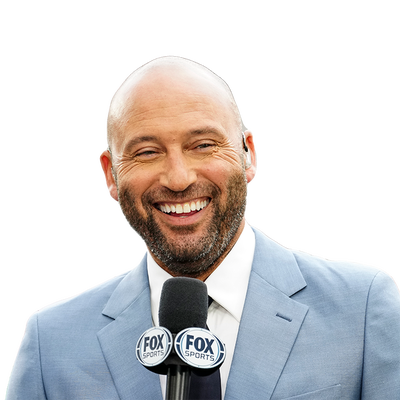

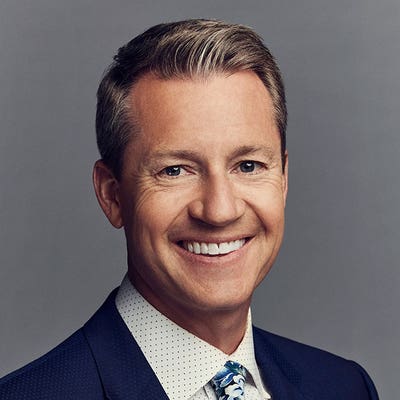

Hasselbeck said he will wear rib pads for the first time this season after suffering fractures last year against San Francisco that sidelined him for two games (“Thank you, Patrick Willis,” Hasselbeck quipped about the debilitating borderline hit from the 49ers linebacker). Hasselbeck remains undecided about whether he will wear a mouth guard despite the urging of teammate Lawyer Milloy and his father-in-law – a dentist.

Hasselbeck knows he would receive additional protection from a mouth injury. But Hasselbeck, who has a Boston accent, believes his audibling at the line of scrimmage would be more difficult for teammates to understand if forced to use a mouth guard. The same problem affected Wiegmann and Rabach because the center position is usually responsible for line calls.

“I always had a mouthpiece in the top of my helmet just in case, but I got comfortable,” Wiegmann said. “Now I can’t even put one in.”

Said Rabach: “It restricts your breathing. You always lose the damn thing or it ends up in your shoe, which is pretty nasty. I understand the ramifications of not wearing one, but I haven’t in nine or 10 years.”

Asked whether he has suffered a concussion during his NFL career, Rabach laughed and said, “I’ve never been diagnosed with one.” Wiegmann has and admits to playing “a couple of games where I don’t really remember the game at all.”

Hasselbeck said he has suffered three diagnosed concussions since high school. Hasselbeck, though, said he was told by a team doctor that there is no absolute proof mouth guards can help prevent concussions. That contention was backed by Goodell and Anderson.

“Until you have more across-the-board validity, it’s hard to force people to do things,” Anderson said. “We have to be realistic in that you’ve got to be able to validate your case before you take Draconian measures. It’s not in our best interest to be Big Brother on things that we can’t justify.”

Said Goodell: “There’s conflicting research on that to some extent. It’s not necessarily proven, but clearly I think you’d be safer with a mouth guard in your mouth.”

Ultimately, the NFL may enact mouth guard and padding rules to save players from themselves and reinforce the higher standards in place at the college, high school and youth levels. Even if there is no hard proof that injuries can be prevented, the NFL is learning the hard way about not proactively addressing safety issues in the past. The New York Times reported that the league is facing potential liability of $175 million for workman’s compensation claims filed by retired players in the state of California. Those claims could grow as health problems – whether football-caused or not -- emerge for a new generation of retired players.

“You obviously want the players or any worker to have the protections required by law,” Goodell said of the California workman’s compensation issue. “You also want to make sure they’re not being misapplied or people are trying to get something they’re not legally required to get … It’s a balancing act.”

So is trying to convince players that more padding is not only in their best interest but also wouldn’t significantly impact their performance or speed.

“If everyone had to do it, the game would be exactly the same,” Chambers said. “Nobody would have an advantage.”

Except possibly being healthier.